The martial arts can be divided roughly into two groups: empty-hand arts and weapons arts. There is an endless argument within each group about which particular empty-hand or weapon skill is superior (i.e. pummeling vs. grappling or sticks vs. blades). But there is a general agreement among martial artists that a person with a weapon, regardless of the type of weapon, has a definite advantage over a person without one.

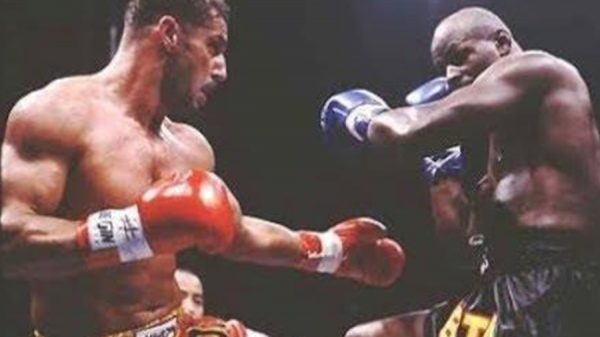

Weapons are better than empty hands for one reason: the ease with which they can hurt another person. In kickboxing matches and bare-knuckle karate tournaments, it often takes a long time for one competitor to knock out another. In many of these fights, both opponents are left standing at the end, and judges must determine the winner. Even no-rules grappling matches often go for 30 minutes or longer before one man triumphs over his opponent.

With a stick, knife, or gun, however, you can hurt someone worse than you can with your bare hands — and in a shorter time.

The effect of the use of weapons on the development of martial arts cannot be overstated. The ability to hurt and kill quickly and easily changed the way ancient masters looked at the world. They needed to make life-and-death decisions in the blink of an eye.

One slash of a samurai sword or one slice from a poisoned kris knife could mean instant death. Ancient masters became spiritual people because they had no choice: They needed some type of heightened awareness to survive in their chosen profession.

The heightened awareness of the ancient masters usually came from the practice of meditation or some kind of ritual trance. These methods of altering consciousness were learned from priests or shamans. This is the origin of the influence of Asian religious traditions on the martial arts.

The warrior needed an altered state of consciousness to see and react properly to an attack with a blade or other weapon. He needed to judge where a cut or stab was going and react with his own cut almost simultaneously. In other words, the swordsman or knife fighter didn’t react (act after) his opponent’s strike; he acted at virtually the same time as his opponent struck. That’s what is meant by the phrase “becoming one with your enemy.”

The priest or shaman was important to the warrior for another reason, too. Having strong religious beliefs lent reason to the warrior’s actions. Knowing that what he was doing was right took away the doubt that causes hesitation. Remember that one slip could mean the end of a swordsman. The warrior in ancient times needed the context of firm religious beliefs to keep his conscience clear and himself alive.

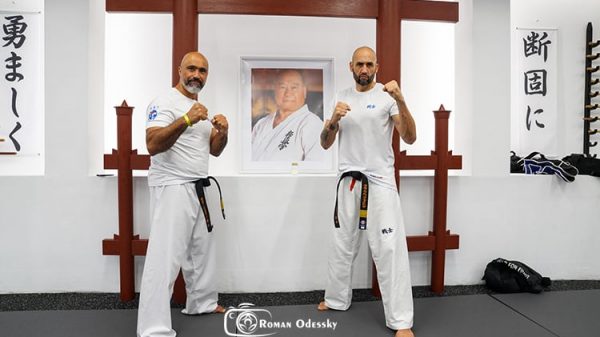

The presence of meditation traditions in empty-hand martial arts is a carry-over from the weapons arts. The empty hand simply is not as dangerous as a stick or sword. In fact, many ancient masters taught empty-hand skills (along with meditation) first and weapons skills second because the empty hand is less dangerous.

That way, it was easier to contain a student who turned on his master. Then and now, a student with empty-hand skills is no match for a master of weapons skills. As Niccolo Machiavelli wrote, “Between an armed man and an unarmed man, there is no comparison.”

Today, we live in a much safer world. Most of us live a relatively quiet and uneventful life. There are no duels of honor with swords or knives. We have no practical reason to seek the altered consciousness of the ancient masters. For this reason, traditional martial arts seem like hopeless anachronisms. But there is something present that is not easily dismissed.

By learning the exact movements of ancient warriors, we gain an insight into a way of thinking that is obscured by the comfort of modern life. No one can truly know what it’s like to fight a life-and-death battle unless he has done so.

We can only taste what it’s like to be a warrior through kata (forms) practice and sport-fighting competitions. Even in these distilled forms, we can still experience the great mystery of the ancient masters — the quiet mind from which their great skill came.

Story by Keith Vargo