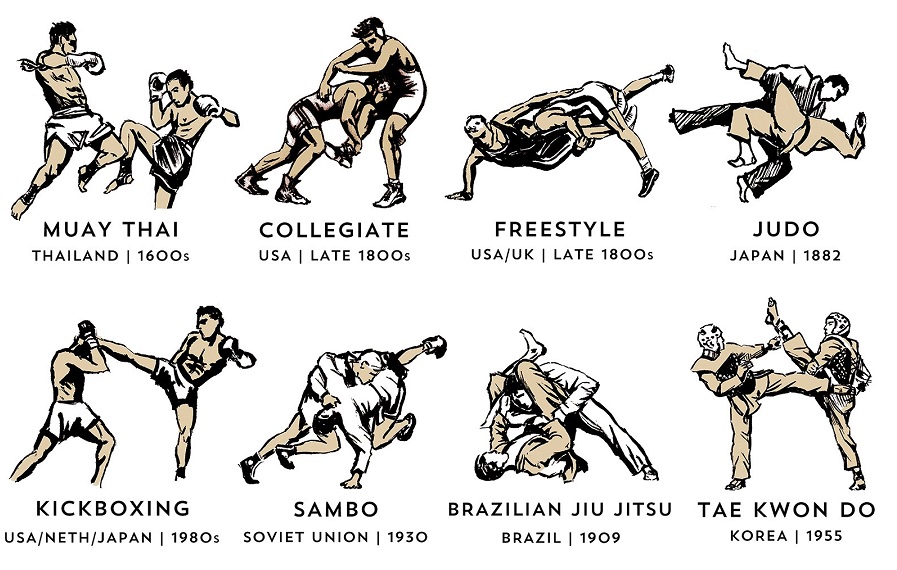

In the era of mixed martial arts, it’s become clear that, whether you’re training for competition or the street, being competent in more than one way of fighting is a necessity. Inside the octagon, some of the most dominant fighters in MMA history—Fedor Emelianenko, Jon Jones, and Anderson Silva to name a few—have also been it is most versatile. Meanwhile, the least adaptable fighters (like Ronda Rousey) end up paying a heavy price when the fight strays outside their realm of expertise.

Because of this, it can be tempting to stuff as many styles and methods into your training as possible. You don’t have to go far to find martial arts schools whose instructors boast black belts (or the equivalent) in an improbable-seeming number of disciplines. But the pursuit of versatility, especially too early in your martial arts journey, often leads to diminishing returns.

A Kick Is A Kick

A Kick Is A Kick

A roundhouse kick in Kyokushin and a roundhouse kick in muay Thai are practically indistinguishable. Both strike with the shin. Both arts have practitioners who can snap a baseball bat in two with the sheer power of their technique. To an expert, the benefit of knowing both comes down to being able to gloat, “I know muay Thai and Kyokushin.” To a novice, this benefit is negligible since they haven’t mastered the basic application of the kick to make it effective.

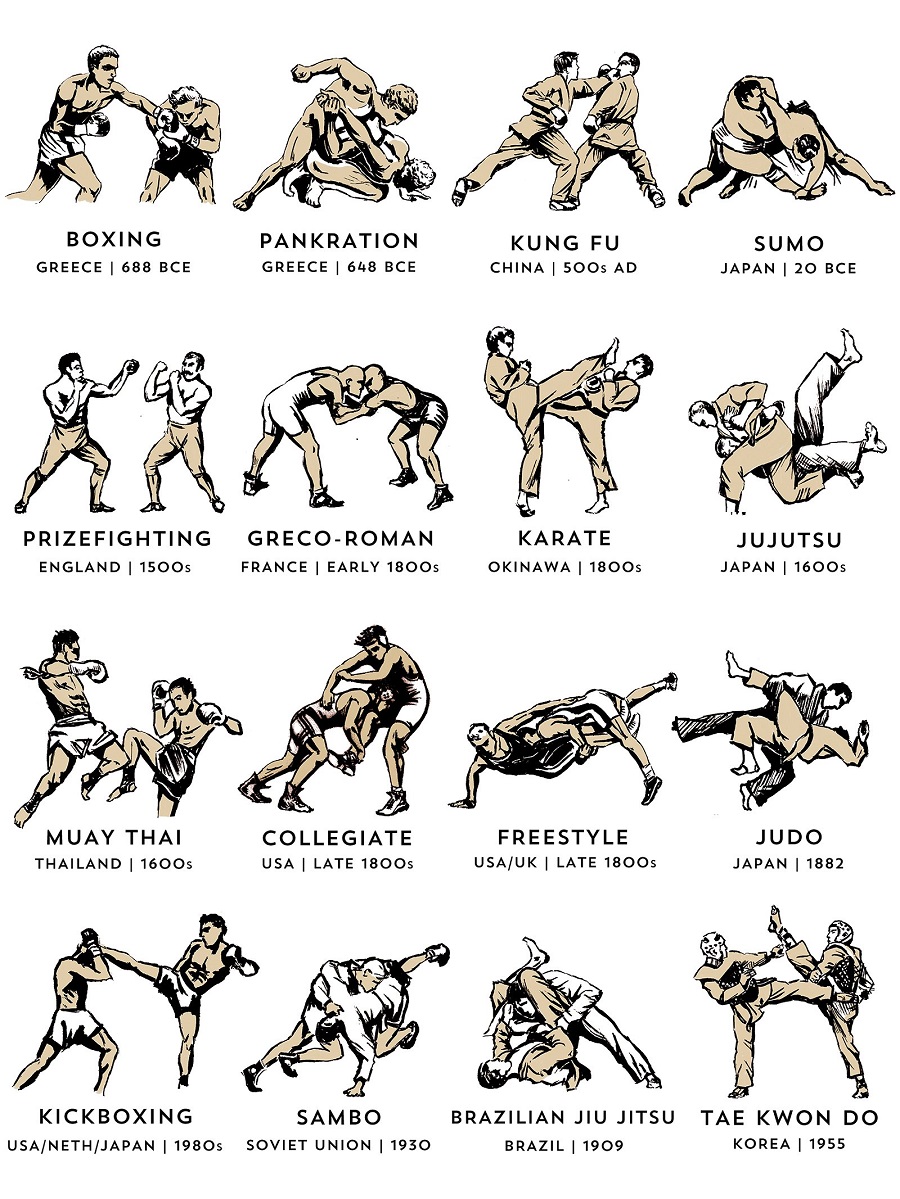

One might say that boxing is better for punching than muay Thai, or that tae kwon do is better for kicking than karate. Fair enough. But this doesn’t mean that cross-training is obligatory. Far from it. I doubt anyone would want to be on the receiving end of a muay Thai uppercut or a karate sidekick. Whatever advantages one style has over another, it usually comes into effect under that style’s rules. A Thai fighter will most likely lose to a skilled boxer under boxing rules and vice versa. When rules are removed, such as in self-defense, it is the practitioner, not the style, that determines the outcome.

Drilling ten different ways to throw a single technique will not lead to a higher level of ability. It often has the opposite effect, especially for beginners.

Get Good at One Thing First (OK, Maybe Two)

Many people cite Bruce Lee as being one of the first people to tout the benefits of learning different styles. But one must not forget that Lee had already mastered one style (Wing Chun) before he started adapting other arts into his own unique fighting method.

It’s human nature to want to one-up the next guy. If you have black belts in judo and karate, someone else will inevitably come along claiming to have belts in Brazilian jiu-jitsu, aikido, silat, and some other obscure style you’ve never heard of.

“I often hear people saying they know seven different styles,” says Hanshi Alex Dunlap of Dunlap’s School of Karate in Gary, Indiana. “To me that’s impossible. To learn one style takes a lifetime.”

This isn’t to say that you should only train or teach one art. Earlier I mentioned Ronda Rousey. When she moved to MMA from judo, she proved herself to be, without question, one of the best grapplers in the world. Her career was cut short when her lack of basic striking skills led to two devastating knockouts. So, it is important whether your base is striking or grappling to have at least rudimentary knowledge of both. But how can you achieve this without overtraining?

The answer starts from within the fighting system itself. Most grappling arts have basic striking components and most striking arts have at least some grappling techniques. But when the focus becomes rooted in one or the other, usually due to competition in sport martial arts, certain techniques are relegated to promotion day or self-defense demonstrations. The first step in bridging the gap between grappling and striking is mastering those aspects of your own system.

Competing Philosophies End in Confusion

My instructor, Shihan Kenneth Kates of Beverly Pagoda Ryu, once told me a story about a former student of his, a sport karate fighter who decided to branch out to kung fu.

“He was a real champion (in that art too),” Shihan Kates said.

That was until his new instructor decided he was too aggressive and set about taming the student’s fiery fighting style. He never won another championship.

“He lost his base and natural instincts,” my instructor explained. “When you study another art, you still have to stay true to your base.”

Studying other styles is good, perhaps even imperative, but doing so should make you stronger as a martial artist. The best reason to branch out is to learn the strengths and weaknesses of different styles, as well as your own. You shouldn’t seek to master everything under the sun. You can’t. But you can know a little about a lot. This way there are few surprises, and in the end, you become better all around.

As teachers, we can sometimes get excited to pass on all our knowledge to eager minds waiting to soak up our experience. We make mental (sometimes even literal) checklists of all the myriad techniques and disciplines we want to teach our students. But no matter how absorbent the sponge, there is inevitable spillage. Mastery takes time. There is no way around that.

You can use other styles to add some seasoning to your practice. Spread yourself too thin, however, and you erode the foundation your skills were built on. The trees with the strongest roots grow the tallest. This remains true in nature and in martial arts alike.

By Marcus Day / blackbeltmag.com