The interview was published on Blitz Magazine, January 2015

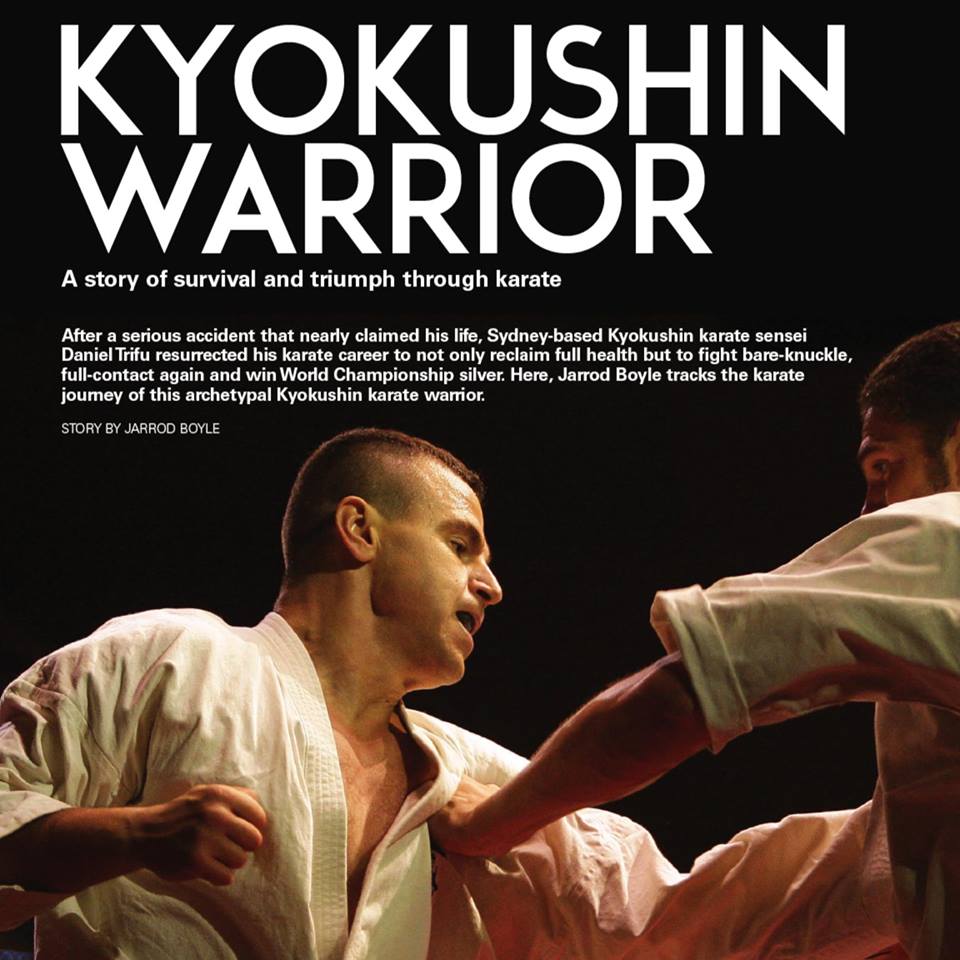

After a serious accident that nearly claimed his life, Sydney-based Kyokushin Karate sensei Daniel Trifu not only regained his full health, but returned to fight bare-knuckle, full-contact karate and win world-championship silver. Here, JARROD BOYLE tracks the karate journey of the archetypical Kyokushin warrior.

“[Daniel’s] mother called a gypsy woman, who was a friend of the family, who came and did incantations over Daniel’s body to get the evil spirits out,” says Lynne O’Brien, partner of Kyokushin karate master, Daniel Trifu.

“Did it help?” I asked. It seemed the obvious question.

“I think it did,” Lynne replied. “The alcohol she put on his chest helped to keep his temperature down. I think it also gave you hope. Just watching him lying there and doing absolutely nothing would have felt worse.”

This occurred in Romania, after Daniel suffered the most crucial knockdown of his first forty years. In his career, Daniel has amassed the greatest number of showings in international full-contact Kyokushin karate events.

His life in martial arts has turned a circle so broad that it encompasses Eastern Europe, Asia and his adopted homeland of Australia.

“I arrived in Australia exactly on my nineteenth birthday,” says Daniel. “That was in 1993. I arrived at Bondi Beach. Bang! It was beautiful. Blue sky like I’d never seen before. It was just an amazing, amazing place.”

Daniel had spent the first nineteen years of his life growing up in Bucharest, Romania, as the son of diplomatic parents. Life in a communist country, ruled by the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu was in stark contrast to life in Australia.

“It was tough,” he remembers. “Food was heavily rationed. You got one kilogram of meat a month; ten eggs a month. No one was starving; you could buy as much bread and potatoes as you liked, but meat and cooking oil were rationed.

“You got television for about two hours a day. And that was all propaganda. People didn’t smile on the street. They put their heads down. Everyone was oppressed. There was a craving for western movies.”

These movies gave Daniel his first taste of the martial arts and the promise they held for a teenaged boy was exciting.

“I remember watching Kickboxer with Jean Claude Van Damme – do you remember Tong Po? I remember the toughness of [those characters]. Around about that time,The Terminator came out. These guys were tough. It was all about coming forward, copping punishment.”

American films made a potent impression on a young man growing up on the mean streets of Communist Bucharest.

“The reason I started [training was that] Bucharest was quite violent. There were situations when I had to defend myself, and I didn’t know how to do it properly. I needed to learn. Other kids would take your money and bash you.

“Bucharest was a different place; you had to deal with [problems] yourself. I remember the school bully used to make me jump to see if there were coins in my pocket. One day, I refused. Guess what happened? After that, ‘No more taxes from you!’

Fighting was a constant necessity.

“There was another occasion when four of them attacked me. I eventually got them on their own. I waited for an opportunity to get them by themselves. We became friends after that.”

Daniel’s mode of conflict resolution has formed his opinions on bullying.

“People have to solve their own problems. Sometimes, you have to train yourself. Some kids have to move schools, [but] I prefer to deal with those problems the old-fashioned way.”

Kyokushin, while a relatively modern style of karate, has strong appeal for people seeking the old-fashioned way.

“I went to a Kyokushin dojo and saw them training and thought, ‘This is good – these guys are tough. These guys take punishment. Other [styles of martial arts are] trying to avoid pain.”

The basic shin on shin, knuckle on bone reality of full-contact karate spoke to him.

“It was a big part of it,” Daniel enthuses. “Their attitude was, ‘What are you scared of? Copping one or two kicks?’ It was also a little bit crazy. I chose a style that I thought was going to make me tough.

[bctt tweet=”Kyokushin, while a relatively modern style, has strong appeal for people seeking the old-fashioned way” username=”kwunion”]

“A style where nothing was going to get to me. In defense, you’re always going to get hit. If you have a strong body, you can take punishment. Why would I be worried?”

Martial arts training was forbidden in Romania under Ceausescu’s rule, which added something to its appeal.

“You weren’t supposed to participate, “ he says. “The message of martial arts is ‘be yourself, be free.’ Ceausescu’s regime didn’t like that mentality.”

In addition to preventing people from arming themselves in any way, the government had forbidden any activity in which people could congregate freely.

“The government didn’t want people to congregate and talk. It was word-of-mouth to get there. Then, when you arrived at training, there were hundreds of people doing it. Amazing.”

Daniel experimented with a few styles before finding his way to Kyokushin.

“I started with Wushu kung fu and Shotokan karate. I thought it was a bit scrambled in Romania.”

“I started training in December, 1989. It was hard to find a school to take me. They’d ask you questions to find out about you. ‘Where are your parents working?’ When they found out my parents were working for the government, they were like, “Get out of here!”

Daniel doesn’t have any difficulty explaining the popularity of martial arts in Romania at that time.

“People loved training. It was a kind of rebellion. I’m surprised I didn’t get in any trouble.”

Once he arrived in Australia, Daniel continued training in Kyokushin.

“I started training in 1993 with John Taylor in Bondi junction. Then, in 1994, Toku Jun Ishi opened a dojo in Paramatta. Myself and a few others that were fighters moved to continue to train with him. We had to travel quite a bit to get there.

“I was living in Mackay, so it was a bus, two trains and a fifteen-minute walk. All up, it took an hour and a half each way. I could have stayed [training] with John Taylor, but I knew that if I travelled, I’d have the best chance.”

It sounds as if just getting to training would have required a great deal of motivation.

“Toku Jun Ishi was a really good instructor, probably the best I’ve seen. He is a genius, really. He was also very Western – a real people-person. People loved him, and his knowledge was amazing.”

Around that time, Daniel had begun to make a living as a bouncer.

“I worked as a bouncer in King’s Cross. It was a tough way to make a living. I was earning between ten and twelve dollars an hour, working four or five hour shifts.”

Daniel credits his work as a doorman as developing a host of qualities, not least of all his skills with the English language.

“Being a bouncer was good for me; originally, my English was sketchy. [Working doors] improved my English, but it also developed my negotiation skills, so that I didn’t need to fight anymore. One day, a bikie gang comes in, and before you know it, they’re walking away, because of my verbal jiu-jitsu.”

That experience of working doors – in addition to growing up in Bucharest – did a lot to inform his attitude to self-defence.

“[Kyokushin] has the elements [of self-defense] in it; it was originally punch to the face and everything. You kick to the nuts; you do what you have to do. People become confused with Kyokushin in terms of fighting and kumite. They are different. I don’t completely agree with the [tournament] rules; you can’t punch to the face.

“Security work is pretty rough and I do the exact opposite of what I do in a tournament – I go for the head. I’d use the techniques prohibited in competition. A lot of instructors miss the point.

“You start with the art generally, and then work within the tournament rules. The best way [to deal with conflict] is to walk away, of course. But that depends on the student.”

Developing a student’s willingness to engage is the most difficult part of teaching self-defense.

“I tell my students, it’s a slap in the face. That’s how the fight starts. You take it from there. He [the assailant] has one million options in how he’s going to start the fight. So many things can happen; will he grab a weapon, will it go to the ground?

“You have to be reactive, and the only way to do that is by having experience and a lot of exposure to the real situation. Most people are not ready for eye-gouging. To survive, I’ll bite if I have to.”

Developing students requires perceptive analysis from the outset of training.

“Everyone’s got an amazing talent at something,” says Daniel. “All of us. There’s a couple of things we’re the best at in the world, but never had the chance to discover.

“Everyone has their own skill. [As an instructor,] you have to find what those skills are. You have to find them and work around that. Make the talent the focus and build them around that.”

[bctt tweet=”Everyone’s got an amazing talent at something, says Daniel, all of us” username=”kwunion”]

Oftentimes, that’s a matter of keeping things simple.

“Everybody wants to be flash. It’s great to have flashy kicks, but you have to have your bread and butter. A samurai uses what is good; he doesn’t try to find something else once he’s bored with it. He uses simple, effective skills.”

Daniel draws on his own example to paint the picture.

“I had an effective low kick. People thought it was boring, so I stopped using it. Then, I lost it. What you have, what you don’t have, you have to work hard on your assets. I have identical twins training at the dojo, and even they are different.

“You have to look for what every single person can do. What are they like mentally? Can you push them? Some people aren’t prepared to take the pressure. You can win tournaments with simple things, but they have to be really sharp and really good.

“We keep pressing fitness, but we don’t all fight the same. Recognizing individual ability for every single person is what makes good fighters.”

Fighting, then, is the clear basis of Daniel’s martial journey.

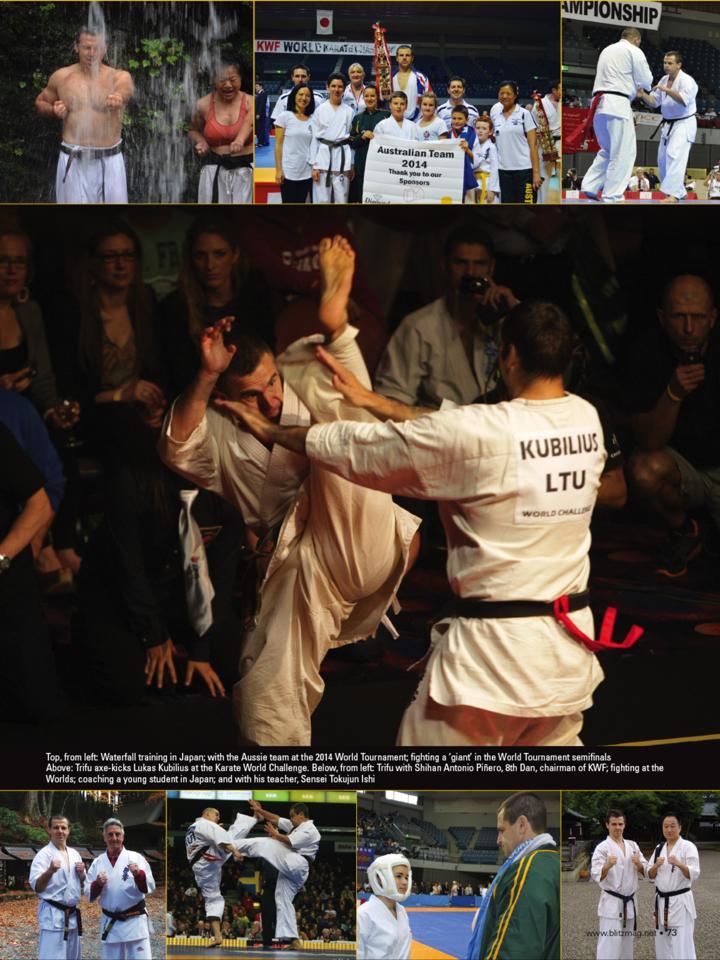

“I’ve competed in eleven international events; that’s the record. I started in my twenties. I’ve competed in every one since [Kenji] Midori won [the fifth Kyokushin Karate World Tournament] in 1991. In my last one, I came second.

“I’m talking world cups, too. They are every four years, so you get one every two. Sometimes, you lose a very close decision. You train so hard, go there, do one round and win, then in the second round you lose; it’s quite depressing. You just have to jump back on the horse and do the next one.”

It’s difficult for most people to understand what makes a person persevere under that kind of dispiriting circumstance.

“I knew I could do it,” says Daniel, “I enjoyed the journey. Every time it’s a new challenge. It’s difficult to be selected. You go, do everything you can and don’t do very well. Two years [between events] sounds like a long time, but time flies.

Next thing, it’s upon you. I’d been going and not getting any major result until the Kyokushin World Federation World Championship in Japan last year. I just kept thinking to myself, ‘I can do this, I can do this.

“I saw all these massive guys at weigh in, and thought, ‘What the hell am I doing here? I’m forty years old. If I don’t do it now, I’ll never do it. I can’t just KO them. I have to play the game to win.

“And that’s different to looking good. Some people don’t care how they win. If the fight is ugly, they get the decision, and that’s what matters most.

“I was the smallest guy there, weighing in at ninety-five kilograms, at about six feet tall. There were a number of massive Bulgarians. One guy weighed in at one hundred and twenty-two kilograms. I basically walked through them.

I took the punishment, gave it back, and found they couldn’t take it. When I fought in the final, the decision was so close it was like flipping a coin. My opponent was the same size as me.”

Twenty years of tournament experience has given Daniel a strong sense of how to approach the competition.

“I don’t care how; I just want to win. You have to be a good tactician to win like that. I’ve got a basic style and I use that to get the win. The guys in the final and semi-final were very good.

“They put everyone away. I cut their weapons off, made them uncomfortable; made them look ugly and stupid and frustrated them.”

Daniel credits the experience of working as a doorman with developing a significant part of his strategy.

“With working doors, part of the skill is understanding people’s psychology. If you see their eyes, they’re actually scared. In the fight, that guy will crack. Some guys [however], you can’t tell. They have a very good poker face.”

After his outstanding showing in the World Tournament, Daniel decided to undertake one of the toughest tests of Kyokushin Karate; the Fifty-Man Kumite, in which a karateka has fifty fights in a row, each fight facing a fresh opponent.

“I did the Fifty-Man Kumite after the world tournament. From the sidelines, people were yelling out, ‘Move! Move!’ I just stood there and wore it. I was injured afterwards, don’t get me wrong. It was my pain threshold that took me through, not the toughness.”

Daniel’s physical condition after the fight also drew a few comments from those involved from the medical profession.

“The doctor from the Polish team said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like that outside a car crash’. I was so bruised I couldn’t walk. Afterwards, I went to train at the famous Mount Mitsumine. I trained and moved like an eighty year old, but I got through it.”

[bctt tweet=”20 years of tournament experience has given Daniel a strong sense of how to approach the competition” username=”kwunion”]

If Daniel’s example is anything to go by, kumite is less a matter of what his opponent can do to him, and more a matter of what he is willing to deem dangerous.

“I’ve never been dropped by anything below the waist,” he says. “The last time I was dropped by a head kick was in 1997. I had two broken ribs in the semi-final of my last tournament, but I got through it.

“Body shots? You go down and stay down and wait for the referee to save you? You’re a pussy! Get up!’ When you fight, you fight like a samurai. You fight to the death.”

Daniel reduces fighting to a kind of personal decision making under extreme duress.

“People have to brave; they have to want to fight and to dig deep. You can’t hold back. Once that happens, you’re not there to win anymore, you’re there to survive and go home safe.

“Most of the time, it’s just a case of ‘dig a little deeper; ten more seconds, three more punches and you’ll win the fight.”

Daniel has managed to escape serious hits to the head in karate competition since 1997, but a nasty encounter with a kerb in a Russian street found him fighting for his life.

“I was getting out of a taxi and I blacked out, fell down and hit my head,” he says. “The ambulance came and picked me up, but after taking my wallet and my watch, they threw me out into the street.

“My friends carried me to the hotel. The next day, I thought I had woken up with a hangover, but it was actually a brain hemorrhage.”

The head injury was so severe, Daniel recalls little of the incident – the impact scrubbed his memory for hours of both before and after. His partner, Lynne O’Brien, was with him at the time and recalls the events better.

“We’d been having drinks at the sayonara party. I thought it was a hangover. Three days later [we were back in Romania] – you’re not supposed to fly with a head injury like that – and the pressure was causing excruciating pain. His mother rang for an ambulance but in Bucharest, the ambulance doesn’t come for a headache.”

It was at this point that things became so dire his family were willing to try anything.

“That was when the Gypsy woman came and did incantations over his body to get the evil spirits out. Daniel couldn’t speak, he was in so much pain. All he could do was to utter numbers for pass-codes for anything he might need. He looked like he was drifting out of consciousness, so we called for the ambulance again.”

Things didn’t improve at the hospital.

“No one spoke English – not even the doctors. His mother had to bribe everyone to get an MRI. Eventually, the doctor came back to us and said he had to operate, by drilling a hole into his skull to release the pressure. I said, ‘Over my dead body! I’m getting the Australian embassy involved. Luckily, we had health insurance.”

After speaking to an Australian doctor, drugs were proscribed which made Daniel hallucinate. “He was seeing crazy things,” says Lynne. “It was like Mickey Mouse on LSD. Cartoon characters with a martial arts feel.”

“I was discharged after a week,” Daniel says. “I didn’t have any sense of taste or smell. I was a bit of a mess. It took about two years to get better. I fought in Japan about ten months after [the accident].”

I’m no expert in head injury, but surely full-contact karate can’t have been high on the list of the doctor’s priorities.

“Every time I’d spar, even from chest punches, I got profuse nose bleeds.”

Even so, Daniel was not to be deterred.

“I fought in the All-Japan Championships ten or eleven months after, and lost in the fourth round against the eventual winner. It was a very close fight to miss the decision.

“The Karate World Challenge was held in Sydney the next year and was televised in Japan. I fought there, too. It was a selection for the World Tournament. I was determined not to let the accident get in the way.”

“I knew there was no holding him back,” says Lynne, “Fighting is his life. If it was taken away… He enjoyed teaching, but the life of a martial artist, the only true way in Kyokushin is through fighting. I knew that – I knew it all along.”

These certainties didn’t provide much in the way of security, however.

“I was scared when he started sparring, ‘No head kicks!’ I used to say. I think he went back too early, but then, no one waits the required amount of time. He was unsteady on his feet for a while, but when you’ve been damaged like that, you’re hesitant for everything.

“He crept into it as slowly as he possibly could. That first World Tournament [back] – I was petrified.”

Lyn achieved her first Dan black belt last year and now they work together as partners in running their own Kyokushin Karate schools.

Now I’m running my own dojo,” says Daniel, “And I make my living teaching people. We’ve got three hundred and fifty members at nine locations and growing.”

“We’re both teaching and training six days a week,” says Lyn.

“I got involved in Kyokushin purely through Daniel,” she continues. “Originally, I was living in Queensland. I moved down here [to Sydney] and did lots of gym and long-distance running, until I had to slow down after I did some damage to my back.

“I decided that I didn’t see enough of him, so I got involved that way. Now, my biggest battle is with Dan so I can go and do a tournament.”