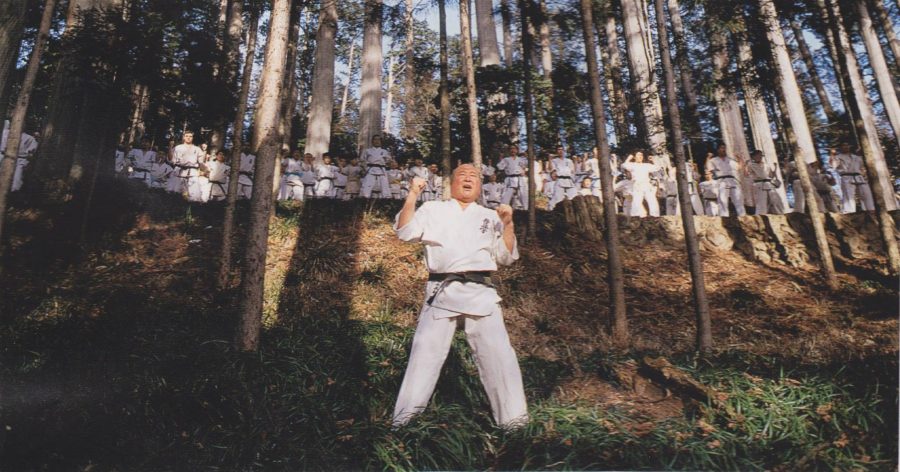

Gichin Funakoshi was not the greatest karateka of all time.

Funakoshi left 20 precepts, a distillate of his karate philosophy. They are engraved on a plaque at his grave at Engakuji, the Kamakura temple where he’s buried. His sixth precept is a window into the character of the man. Kokoro wa hanatan koto o yosu. “Be able to release your mind.” That’s a poor translation, but it’s challenging to come up with a more accurate one. The idea is that you should not be so rigid that you can’t adapt to changes in circumstances that are part of life. More than two centuries before Funakoshi’s era, the concept of marobashi was described by Yagyu Sekishusai, founder of the Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, as a core element of his school of strategy. In part, marobashi describes a “rolling log,” and it refers to the ability to cope and adjust and exploit circumstances in life that change as quickly as a log rolling down a slope.

But Funakoshi was quoting a Chinese philosopher from centuries before that. Shao Yong (1011-1077) was a Confucian thinker who lived during the Northern Song dynasty. As a classically trained scholar, Funakoshi was familiar with Shao Yong’s writings; he incorporated a line from the philosopher’s poetry in his precepts. To be able to release one’s mind from an inflexible frame would have been important to a man in Funakoshi’s circumstances. Think about it: Funakoshi went from tiny, quiet Okinawa to bustling Japan, a land that was only a couple of decades past a violent uprising, the Satsuma Rebellion, during which dissatisfied samurai sought to overturn the new imperial government and along the way threw the whole country into turmoil. The Japan of the early 20th century was the scene of fierce politics, with communists and labor-union workers frequently brawling in public. There was tremendous energy in the debate over Japan’s future, with the military insisting on an expansionist course (that would soon translate into Japan’s invasion and occupation of Korea) and industrialists and others seeking a more isolationist approach. Demonstrations often spiraled into riots; political opponents were frequently beaten and assassinated. It must have seemed like an apocalypse to Funakoshi.

Funakoshi was also alone. He’d left behind his wife and two of his three boys. The food, the language, the customs — all of it would have been at least slightly unfamiliar to him. Additionally, he was trying to introduce his foreign (to the Japanese) art. Most karateka knows this, but they may not understand just how difficult that task was. Okinawans who lived in Japan were not even considered full citizens. Further, karate was seen as a crude system when compared with the elite warrior traditions of Japanese budo. Imagine going to Burgundy, France, home of some of the world’s great vintages, and trying to market some homemade dandelion wine you’ve cooked up in your basement. That would have been what it was like for Funakoshi to introduce karate in Japan. Funakoshi owed a huge debt to judo founder Jigoro Kano, who took an interest in karate and provided introductions and facilities that allowed Funakoshi to bring his art into the mainstream of Japanese budo. Even so, it was an uphill climb. Karate, for many years in Japan, had to fight against the image it had, one of being something that was used by thugs and lowlifes. Funakoshi also had to deal with critics back in Okinawa. His “Japanizing” of karate was met with animated disapproval. Funakoshi adopted Japanese names for kata. He brought teaching and training in line with Japanese customs. Traditional Okinawan karate was taught informally, but Funakoshi, once in Japan, introduced the notion of group practice, with rows of exponents moving in unison, which was similar to what was seen in kendo schools. (Nearly all the Osu! and Hai, sensei! utterances have their roots in this period, when the influence of the Japanese military came to dominate the world of budo.)

Every Japanese and Okinawan of Funakoshi’s generation lived through amazing changes, including the devastation of the Second World War. Through it all, Funakoshi managed to persevere, to achieve his goals. He was not, technically speaking, the greatest karateka of that period. He was, however, a giant in his accomplishments. Many of those accomplishments were achieved through his ability to be flexible, to be ready to adapt. He was prepared, at all times, to release his mind.

By Patrick Sternkopf